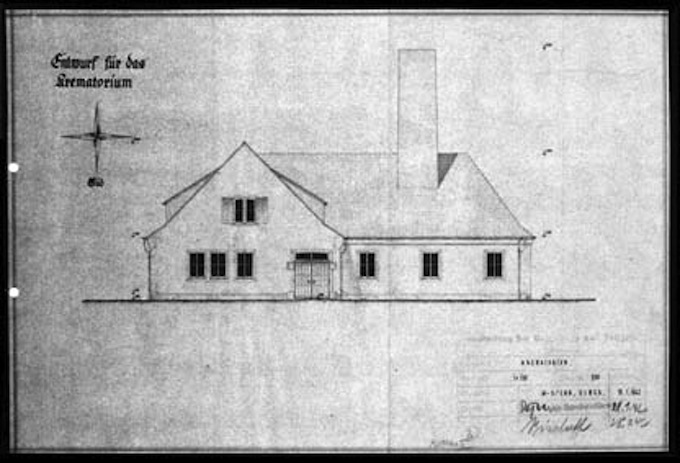

It looks like a mock Tudor house in an upscale American suburb except for the extra tall chimney and the gate across the front door. This is the architectural plan for a crematoria in a concentration camp called Auschwitz.

Elevation of a crematorium

During the approximately two and half years that the camp was in operation, 1,000,000 Jews were killed, as well as 100,000 Soviet prisoners of war, gypsies, Polish political prisoners, and other non-Jews. During 1943, the death toll reached as high as 10,000 inmates in a day.

Seventy years ago this week the camp was liberated. Even with the benefit of time, the hundreds of books, films, and museum exhibits that have been produced to try to explain what happened, and the attempts to commorate the dead, the numbers are still staggering; almost impossible to comprehend.

The inability to mentally absorb the scale of industrialized killing at Auschwitz has plagued our understanding of the camp from the start. As the scope of the mass murder system slowly began to become clear to the Allies during the winter of 1945, reactions ranged from stunned disbelief to outright horror. Anxiety about the human ability to understand such brutality arose simultaneously with the awareness that such brutality had taken place.

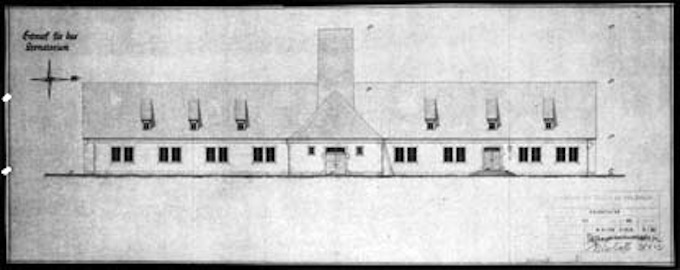

Elevation of a crematorium

When the US military discovered slave labor camps during the winter and early spring of 1945 they took a visceral, hands-on approach to bridging the gap between an abstract notion of the killing and the reality on the ground. Generals Eisenhower, Patton, and Bradley toured Ohrdruf personally. They took in the emaciated dead, their bodies crawling with lice (Patton vomited behind a barracks building). When Ike spotted an American soldier accidentally bump into a German guard and then laugh nervously, he fixed him with a cold stare. “Still having trouble hating them?” he was reported to have said.

The next day, Eisenhower ordered every nearby military unit not engaged at the front line to tour the camp. “We are told that the American soldier does not know what he is fighting for,” he said, “Now, at least, he will know what he is fighting against.”

Bipartisan Congressional tours followed soon after, as did a committee of distinguished journalists, headed up by Joseph Pulitzer. He spoke for many when he admitted his initial disbelief. “I came here in a suspicious frame of mind, feeling that I would find many of the terrible reports that have been printed in the United States before I left were exaggerations, and largely propaganda.” After viewing the camps, he wrote, “They have been understatements.”

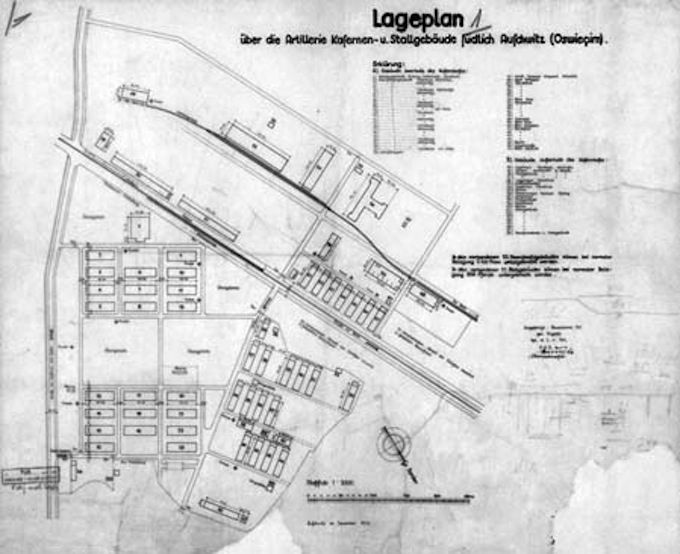

Site plan of the barracks

The pattern of reaction, initial skepticism followed by colossal disbelief, was echoed in the response of even the most hardened of military journalists, such as the young Andy Rooney, who was then writing for the miltary newapaper Stars and Stripes. “I think the American soldiers were stunned, as were the reporters who got into those concentration camps. The extent to which the Germans had set out to destroy the Jews was just incredible. We had no idea.”

The dilemma of comprehending what had taken place even plagued the lawyers whose job was to put the Nazis on trial. Whitney Harris, who had assisted the prosecution at Nuremberg, took the crucial confession from Rudolf Hoess. Hoess explained to him in detail how the system of mass killing at Auschwitz worked. According to Harris, Hoess was not evidently a monster or a lunatic, but was more “like a grocery clerk.”

Hoess lived with his family (he had five children) on the grounds at Auschwitz. “He struck me as a normal person,” Harris recalled. “He was cool, objective, matter of fact: this is my war duty, I did my war duty. It was like I had to go out and cut down so many trees and so I went out and took my saw, and cut the trees down.” Harris found it incomprehensible that the same person could oversee the death camps by day and return to his family at night. Later in life, Harris regretted that he never probed Hoess about this haunting incongruity.

When the Allied soldiers who had witnessed the camps returned home, their reports were sometimes met with anger and denial. One soldier recalled that after showing his wife photographs of what he had seen, she tore them up. In England, people walked out of the movie theaters rather than watch the newsreels. Allied soldiers blocked the exits and forced the patrons to “go back and face it.”

++

How do we, decades later, face it? Often it is by seizing upon individual stories of bravery or survival. These stories shape the experience of the camp into more manageable terms, with a beginning, a middle, and an end, and thus help make the almost incompressible somewhat more understandable.

Another means toward comprehending the horror of what happened has recently become available. In the past decade or so, the archives of the former eastern block countries have been opened and have made it possible to reconstruct—for the first time and in exacting detail—the awful mechanics of what occurred at Auschwitz.

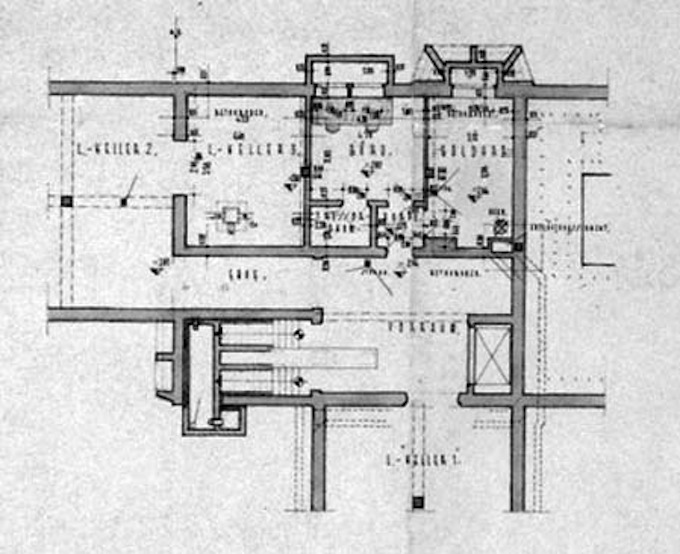

Blueprint of crematorium basement

Blueprint of crematorium basementWe can now, in effect, construct a biography of a place. The specific plans and dimensions, instructions and commands, routes and timetables of the horrendous deeds committed there can now be accurately assembled; the decisions and choices that informed the running of the camp reconstructed. As a result, the story of the emergence of a system of unparalleled human destruction can now be traced.

There are some people who would like to forget that such a place as Auschwitz ever existed. Seventy years later, it is imperative to continue trying to comprehend how such a place had come to be.