Courtesy of Matt Tomasulo

Design firms angle to get hired by candidates and governments. Individual “tactical urbanism” designers strive to intervene usefully in the built environment.

What designers don’t seem to do so often is go all-in on trying to influence civic systems by, say, running for office.

So I was fascinated when Matt Tomasulo told me he was doing just that—campaigning for an at-large seat on the Raleigh, North Carolina, city council.

I’d just written about his organization Walk [Your City], which started as an unsanctioned design intervention in Raleigh, and has evolved into an established program working directly with municipal governments. (My newish column City Tech, for the quarterly Land Lines, explicitly seeks such examples of technology and design successfully working with, rather than around, policy-makers.)

Spoiler alert: Tomasulo lost. But for a complete newcomer to politics, he fared surprisingly well. And his willingness to pursue the goal of diving into the policy-shaping process strikes me as notable—even laudable.

So a couple of weeks after the polls closed, we talked about why he did it, and what he learned. To be clear, what follows is not a journalistic account of a Raleigh election; it’s a summary of our conversation, geared toward the subject of a design-thinker deciding to seek office.

WHY RUN?

Thirty-three-year-old Tomasulo holds a masters in city and regional planning from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and another in landscape architecture from North Carolina State University. While one of his advisers at NC State was also an assistant city manager, he never considered working within government, let alone running for office.

He has, however, become a fervent Raleigh fan since moving there eight years ago. “There’s a lot of energy and momentum,” he says; among other things the city’s downtown core has gone from sleepy to fairly vital. Walk Raleigh was Tomasulo’s tactical-urbanist contribution to that trend: guerilla wayfinding signage revealing the overlooked walkability of the city center. The project was included in the Spontaeous Interventions exhibition at the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennale. And it led to Walk [Your City], which—after Kickstarter fundraising and a Knight Foundation grant—made customizable signage templates available for use in any city or town.

Along the way, Tomasulo found that making tangible change often entailed working with the right government allies—or “herocrats.” And over the past year, he’d begun to wonder about some of his own local government’s decisions. A proposal for a bike-sharing program was voted down by the council. (Tomasulo is enthusiastic about similar programs he’s experienced in cities from Chicago to Chattanooga.) He also felt a major rezoning process was badly communicated: “This could have been such a positive experience for the city,” he says. “And instead it became an incredibly negative one.” Similarly, he was puzzled by what seemed like a non-inclusive official response to complaints about drinking downtown. (More on that later.)

Perhaps underlying all this, Tomasulo wondered if the views of Raleigh’s changing population—the city is growing, and getting younger in the process—were being represented. “It’s not that one constituency is bad and the other is good,” he says. “It’s just another perspective.”

“Current leadership has done a great job,” he adds later in the conversation. “But a lot has changed—in Raleigh and everywhere.” Thanks to Walk [Your City], Tomasulo has witnessed that change: startups, organizations like Code for America, progressive municipalities making smart use of new technology and experimenting with new programs (like his), and so on.

Still, why not just continue to work from an outside influencer or even activist perspective? From the sound of it, Tomasulo’s experience revised his general view of city government’s potential. “I saw it as an incredible platform,” he says. “Working with all these different communities, through all the partnerships and relationships and clients, I feel like I’ve built up a real knowledge base to introduce new ideas – and could use use my design background and experience.” But he would be using it “in a much more realistic way,” he continues. “So I’m not just this person who’s saying ‘this is what we should do.’” In short: He could continue to offer new ideas, but from “a position of authority.”

THE CAMPAIGN

Tomasulo filed for his run on July 17—the last day he could do so for the October 6 election. He had talked to some “current leadership,” and at least a few seemed “somewhat supportive of me running.”

Then his education began. “I quickly learned that there are serious alliances and teams,” he says. “Understanding where the votes lie is powerful.” Next he faced “the harsh reality that you need money.” Specifically: A consultant told him he’d have to raise $150,000, much of which would be spent on direct mail, along with Facebook ads, yard signs, and collateral like bumper stickers. Ultimately, he’d need to “get in front of 40,000 people four or five times in the final two weeks of this campaign,” he was told.

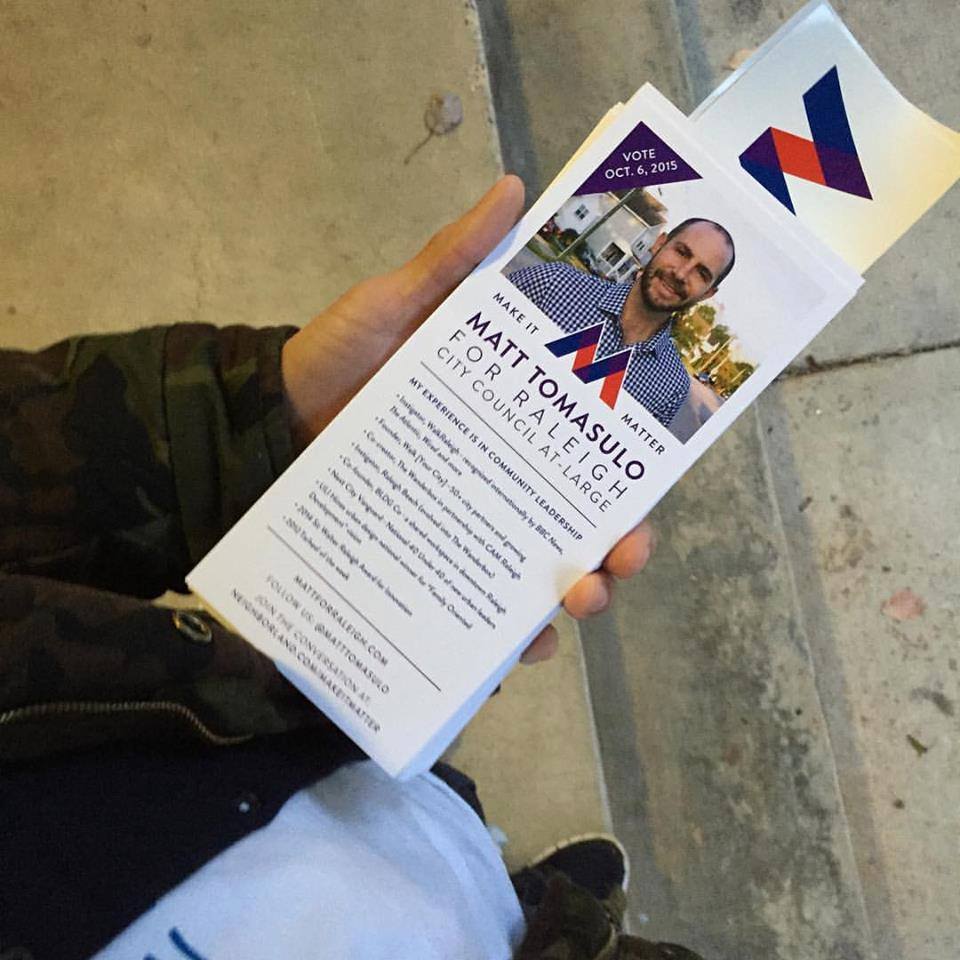

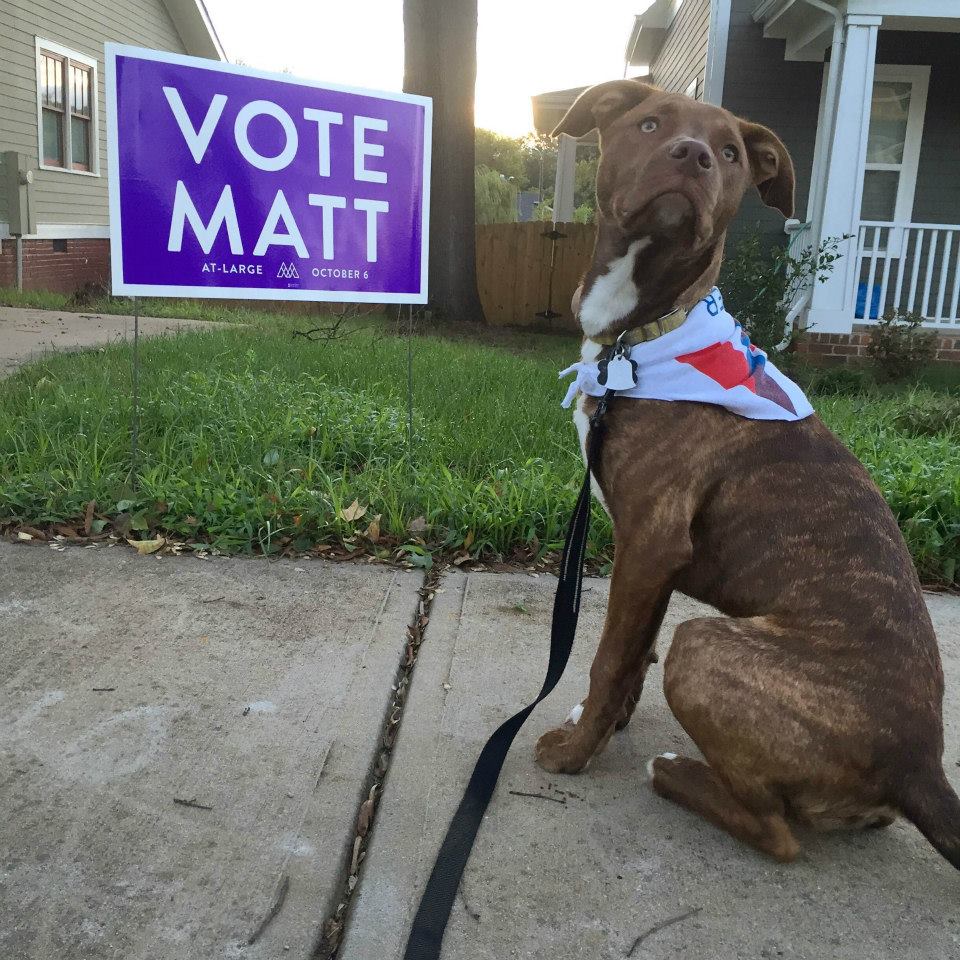

From Tomasulo's Election Day album on Facebook.

Via MattForRaleigh.com.

He ended up raising about $65,000 from individuals, plus donated services, notably from local design firm Creative Offices Of. “I had to create a platform,” he says. “I didn’t want a platform. ‘I’m Matt! People see what I do!’ But I learned that plenty of people really don’t see what I do, or understand how it relates to why I’m running. So I had to go through this whole process of figuring out what it is I represent, and how that is interpreted.

“It was challenging,” Tomasulo continues. “I had to put myself in a box, and say the same thing over and over and over again.” Meanwhile, he started taking meetings with anyone who wanted to talk. He organized fundraisers, and dreamed up online and offline strategies.

To some extent, “it really was a design project.” Aside from actual campaign graphics, that meant guerilla-like (but legal) tactics such as installing mini-billboards at high-traffic intersections on property owned by supporters. A late, second round of yard signs were a simplified version of the originals, reading just: “Vote Matt.” (“People asked, ‘Why did you do that?’ ‘Because you noticed it!’”) A “Pledge Your Pixels” effort encouraged supporters to use special Facebook avatars, even if they couldn’t afford to contribute. A video promoted with a paid post on Facebook got 89,000 impressions, 638 likes, and 150 shares. The campaign even distributed an amusing GIF featuring Tomasulo karate-kicking across a skyline.

Matt Tomasulo for Raleigh City Council At-Large #makeitmatter from Matt Tomasulo on Vimeo.

![]()

Plege Your Pixels options via MattForRaleigh.com

Via Tomasulo's "Painting Signs With Friends!" Facebook album.

Still, the gritty lessons of a local campaign rolled out in real time. “I didn’t really understand it until the final month,” he concedes. “I needed to be super organized, and have all the money lined up. There were events every single night, for weeks straight. I just couldn’t fully comprehend the amount of time it would take. My wife and I, as the campaign team, we didn’t have anybody researching what was most worth my time, so I just kind of went from my gut.” Sometimes that meant a house party where a half-dozen people showed up.

Meanwhile, he got dragged into the dispute over downtown drinking. A local businessman’s campaign warned that the city center was becoming “drunktown,” and while the alarmist ads were mocked in social media, Tomasulo was one of the candidates tagged by the effort as a defender of supposedly problematic sidewalk drinking and dining rules and practices. Again, this is not the place to delve into the vagaries of Raleigh politics, but Tomasulo felt it ended up making him look, to some voters, like a young troublemaker.

In the end, he got 14,845 votes—about a quarter of all votes cast for the two at-large council seats—finishing about five percentage points behind one the two multi-term incumbents who returned to office.

From Tomasulo's Election Day album on Facebook.

THE AFTERMATH, AND BEYOND

Tomasulo’s overall attitude, as he recounts the experience, is surprisingly upbeat. “I think it has totally informed the trajectory that I want to take going forward,” he says—as a designer, and as a potential future candidate. (Supporters have told him to try again in 2017, and even some “state level” politicians have been in touch, he says. And a week or so after we spoke, he was nominated for a spot on the city's planning commission)

Partly he is pleased to have inspired a lot of young, first-time voters. (About seventy percent of Raleigh’s population is now under the age of forty-five, though most who vote are older.) And he was heartened to receive respectable and in some cases passionate support.

But Tomasulo says the most important part of the campaign process involved the people he met, and the conversations he had. And I think that’s worth pausing over.

The experience, as he describes it, brought him into direct contact with a cross-section of Raleigh—from active citizens in working-class neighborhoods to powerful real-estate investors, and many others who may have had little in common beyond a desire for their city to thrive. He learned to take local forums seriously, and found it was possible to identify common ground with very different people.

It’s one thing for a tactical urbanist project or design intervention to purport to be in the best interest of all, or even for a consulting design firm to conduct research before advising a government client. There is a place for those approaches. But actually courting support, door to door, and face to face, with people who may have no understanding of your past work, motives, expertise, or agenda, is a task the intervener can skip, and the adviser can gloss. The officer-seeker lives or dies by it.

It seems instructive that living that rather humbling reality seems to have left Tomasulo energized, despite the outcome. “There are more opportunities to have a lasting impact in Raleigh, regardless of whether I’m on the council.” There are other organizations that could be created, other helpful projects to undertake. By listening and communicating like an officer seeker, Tomasulo learned to learn in a new way.

“So that,” he says, “was super rewarding.”

This essay was originally published in November, 2015.