When I was a music-mad youth with no money beyond what I needed for rent, food, and the weekly purchase of an inky music paper, I ached with the impossibility of owning certain records. My inability to buy these artefacts turned them into objects of mythic unattainability—jewels that could only be enjoyed by reading about them in the music press, or occasionally hearing them on late night radio shows.

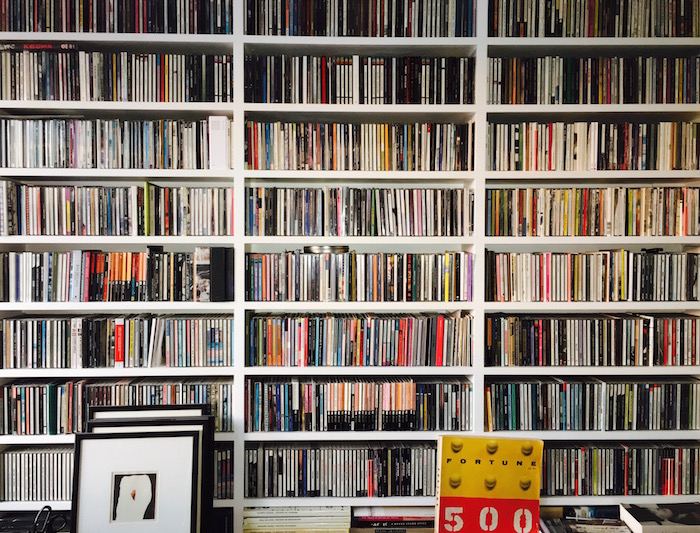

Later, when I could afford all the music I wanted, I built up a vast collection of CDs, LPs, and tapes. I enjoyed hunting for them; I enjoyed the search for the stuff that really mattered to me. And now I have floor-to-ceiling shelves packed with CDs. I have enough vinyl records, picture discs, and box sets to open a small record shop. And I have shoeboxes full of long forgotten audio formats—minidiscs, DATs, SACDs, CD-Rs, 3-inch CDs, and promotional memory sticks.

But today these trophies of my musical infatuation lie untouched, forming a sort of silent mausoleum to my long-standing obsession with music of all kinds. And as they slowly acquire the dull patina of neglect, my musical needs are served by the new online streaming services that offer a cosmos of music in exchange for the physical expenditure of a few keystrokes, and a small monthly fee.

Yet this accessibility to everything has not led to an increase in my interest in music. Instead, it has resulted in a gradual unmooring of my connections with the music I love. I feel a mild sense of dislocation and disaffection from the world of music—a world that, for me, dawned with a virulent obsession with teenage pop and eventually led to an enchantment with the string quartets of Arnold Schoenberg, the cosmic jazz of Sun Ra, the bone-dry electronica of Boards of Canada, and myriad other examples of radical musical expression.

The streaming sites have taken away the ache of not owning. And I now realize that the ache was the attraction. It was a combination of the search, the wait, and the delayed gratification that made the records great. What do you crave when you have everything, except perhaps a craving for craving?

That’s not all streaming has taken away. Let’s put to one side the deleterious effects of audio compression, the thing I miss most is the sense of personal discovery that comes with hanging about in record shops and at record fairs. In his book Every Song Ever: Twenty Ways to Listen to Music Now, the New York Times music critic Ben Ratliff writes: “Listening to anything, especially when you haven’t heard it before, is a highly creative act; but a little less so, I think, when you let the computers do the choosing for you, when you listen through if-you-like-x-you’ll-like-y recommendation engines, based on your perceived listening patterns, and whatever else your streaming service may know about you.”

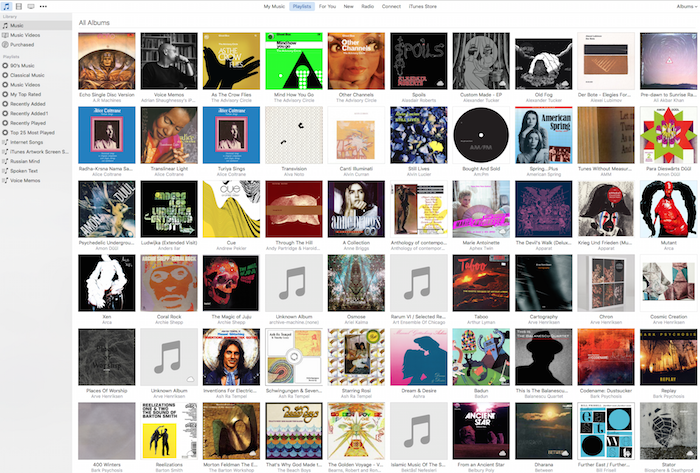

Algorithmic recommendations have led me to some interesting discoveries, although far fewer than I got from good music writing or the recommendations of flesh and blood friends. I’m also forced to wade through some screwy algorithmic selections – stream a Peggy Lee track and Celine Dion might turn up in your you-will-like-this box. Far from extending choice, the algorithmic deejay behind the screen restricts choice by sheep-herding users into musical cul-de-sacs.

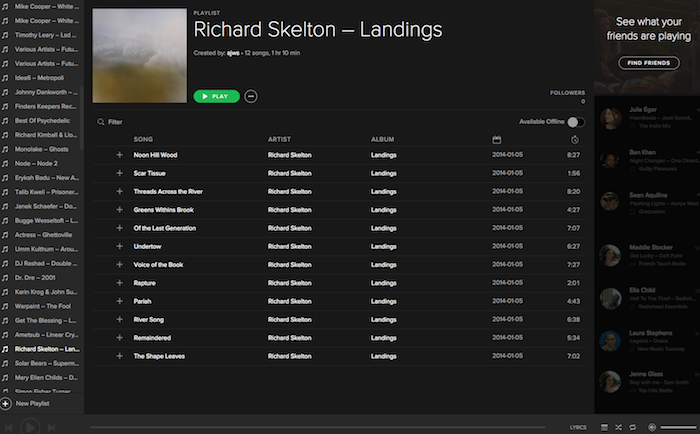

The greatest cause of my dislocation, however, is the contextual thinness of streaming services. It can be argued that music is an immaterial experience, and can be divorced from what Ben Ratliff calls the “metadata.” He writes: “Online listening, great as it is, hides the metadata from you. The tiny amount of information you are given is rendered uniformly in the streaming service’s typesetting and format.”

Only getting a “tiny amount of information” is exactly what I find so disengaging. I want credits. I want biographies. I want criticism and expert reflection. I want the music and not a database sitting on an air-conditioned server farm. But just as music on radio has been neutered by computerised playlists, the personal music stations we all carry around with us have also been taken over by machines.

I’m listening to Spotify as I write this—Laurel Halo, in case you’re interested. Later I’ll look up something on You Tube. I might log onto Tidal or SoundCloud. I’ll do this because streaming has made even loading a CD seem like hard work. And anyway, I’m pushed for time, not to mention stuck on my computer for the rest of the day.

But because I no longer have the ache—the pain of wanting that which I cannot have—listening to music is not the semi-miraculous experience it was once. Streaming sites have resulted in the suburbanization of music.

Comments [3]

03.15.16

07:26

03.15.16

08:13

03.15.16

09:43