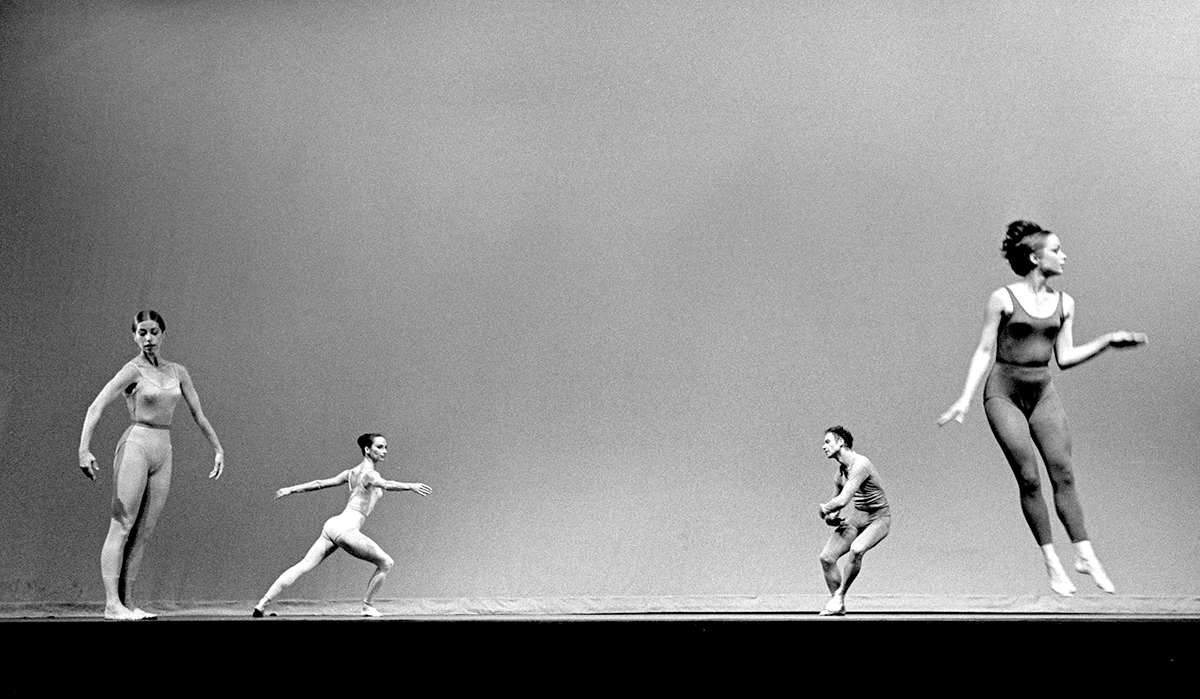

Merce Cunningham, Suite for Five, 1952. Courtesy Walker Art Center, Merce Cunningham Dance Company Collection.

Public space is where we live. (Or used to.) It’s where we seek and discover all matter of stimuli—some of it social, some of it spatial, and all of it deeply contextual—for a world we now only minimally inhabit.

But public space is also empty space. Freedom is on hiatus, travel is on hold, and the very concept of gathering is imperiled. What becomes of that space when we’re absent from it, when our familiar human constellations cease to exist?

Put another way: to the degree that we take our cues from a complex network of public and physical interactions—what happens when the entire network goes down?

Time to reboot the network. And to redefine what it means to assimilate.

We’re often told that assimilation is akin to submission, subjugating independence in favor of belonging. (Not a very Emersonian premise.) But assimilation is also a creative practice, the art of witnessing and choosing, of experimenting, even appropriating as an act of personal reclamation. (A distinctly Emersonian premise.) It’s less a function of alienation than an expression of agency, taking stock of what you see and choosing how to respond in new, and unusual ways.

At its core, the physiological definition of the word assimilate—to seep into and make part of the body—means you are digesting something, metabolizing it, and making it your own. (If simulation is about aping form, assimilation is about absorbing it: integration, not imitation.) Assimilating is visceral, temporal, and physical, requiring an almost animal response: you have to roll around in it, let it slap you around a little, and get messy.

Time to get messy. And to redefine what it means to include your body in your work.

Consider the story of the young, aspiring author who deliberately typed all three hundred-plus pages of The Sun Also Rises, simply because she wanted to feel Hemingway’s words coursing through her fingers. She assimilated his references, internalizing them, touching every word. This is a perfect example of creative assimilation: the idea that you submit to someone else’s story, not to steal their vision or siphon off their voice so much as to dance to their melodies.

The American architect Deborah Berke recently observed that the realities of social distancing will dramatically impact how we make sense of the physical world, simply based on how (and where) we’re meant to move our bodies. Architecture, she suggests, may well be defined in the immediate future by a new, as yet unknown kind of interpersonal choreography driven by many things, not least of which are public health protocols. I think we're going to start as humans to gauge space around us, Berke explains, and judge our movement through space accordingly.

Time to reclaim the present. The key phrase here might be to start as humans.

Progress here begins by declaring a moratorium on bemoaning the past. (The past is never dead, wrote William Faulkner. It’s not even past.) There will be building, and rebuilding. New as yet unknown forms of art and expression will reveal themselves, new networks will come forth, and new voices will emerge.

This world, wrote Emerson, belongs to the energetic.

To assimilate new behaviors and recalibrate new expectations and invigorate new ways to express all that humanity is hard work. For now, we stand still, and we stand apart, suspended in time and stillness, but connected to our bodies, to our humanity, to a greater public space, which is our collective future.

And one day soon, we will all dance together again.

The Self-Reliance Project is a daily essay about what it means to be a maker during a pandemic. Sign up to get it delivered to your inbox here.