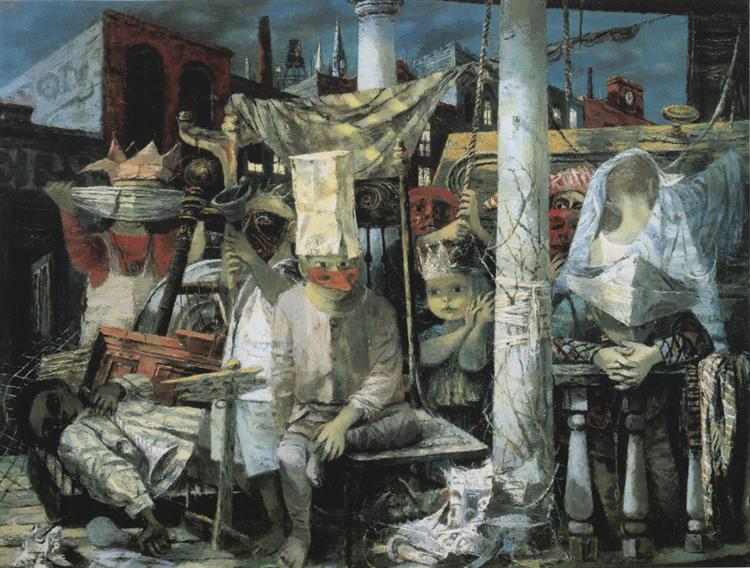

Philip Guston

If This Be Not I

1945

Painted several years before he went to Rome as a fellow in painting at The American Academy (and before his work shifted away from representation), the title is based on a fable about an old woman who questions her identity after changes are made to her outward appearance by someone else.

A decade ago, while in residence at The American Academy in Rome, I purchased (and within an hour, managed to destroy) a very expensive piece of hand-made paper. I felt totally inept, and later confessed as much to the sculptor in the next studio.

“Be gentle with yourself,” she replied reassuringly, “with time and materials.”

The lesson? That self-forgiveness is more productive than self-pity. And that what you make might matter less than the acknowledgment of your own capacity to make it. Those of us with a hard-won studio practice know this implicitly, but others may need a reminder.

So here it is—straight from Ralph Waldo Emerson.

That which you are, Emerson wrote, is the cumulative force of a whole life's cultivation.

Consider the idea that you have put in serious time leading up to this moment. You’ve been feeding your mind. You've been training your eye. You’ve been planting the seeds, tilling the soil, and cultivating the land.

It is now time for the harvest.

Harvesting, an agricultural notion, began as a seasonal conceit (as in harvesting crops) which are cultivated to grow but also—and this is key—to regrow. To harvest, after all, is to reap what you’ve sown.

Now, consider the design principles of permaculture: regenerative, restorative ecosystems that have as much to with sustainability practices and habitat integration as they do with diversity, stewardship, and community resilience. Most of all, permaculture is a philosophy of working with (rather than against) that thing called nature. And nature right now obliges us to stay indoors, working in our makeshift studios, and, yes, going it alone.

For anyone brainwashed by the promises of co-creation, trust me: this is good news.

The South African painter and poet Breyten Breytenbach once likened a notebook to a seed-bed, making the case for journal keeping as an essential act of self-awareness. (Harvesting as collecting.) The American artist Anne Truitt wrote about the glories of solitude and the idea that time alone allowed for a “sieving of experience”. (Harvesting as filtering.) It’s not about the best piece of paper, the fastest connection speeds, or even (or especially) about other people right now, but about focusing on where—but more critically, who—you are.

There’s no wrong way to do this, but you’ll need to do it on your own: that’s the mindset. Studio practice is, fundamentally, a solo endeavor.

So, for what its worth, consider this.

Many years before my own time there, the artist Phillip Guston was in residence at the American Academy in Rome, where he struggled with his own studio practice, and asked himself this beautiful, seminal question.

What kind of work would you make if you thought no one was looking? Make THAT work.

Which he did.

And so should you.