Two years later, he came with his friend Laurie Mallet (then president of the clothing line WilliWear), and hung out for several days. He was in great spirits, about to start teaching again after a long lapse, this time at Cooper Union in New York. He showed us sketches for the book he was preparing on his work and philosophy. We pored over the pages, fussing about the wording, debating the sequence. The book was published in 1994: a beautiful compilation of his work and writing covering thirty years. That fall he unveiled a traveling exhibit (which travels to this day—it most recently opened at the AIGA Gallery in New York City, in the fall of 2014.)

Four months later he was in the hospital. He died in July 1995, twelve days short of his fiftieth birthday, of AIDS, an illness he had concealed for almost a decade. His death, at the height of his creativity, was a tragic loss. For over half of his life we watched his curious and influential career unfold. Now, twenty years later, the AIGA has recognized Dan’s influential career with its highest honor, the AIGA Medal.

Though our relationship was close and comfortable at the end of his life, it wasn't always that way. What follows, over several installments this week, is a personal view, an attempt to fill out the picture he offered in his book and exhibit.

++

We shadowed Dan before we actually knew him.

In March 1967, Esther and I got married and decided to take our honeymoon in Switzerland, then the mecca of modern graphic design. Because I had recently met students from the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm, the German school that had inherited the mantle of modernism from the Bauhaus, we decided to visit it on our way to go skiing.

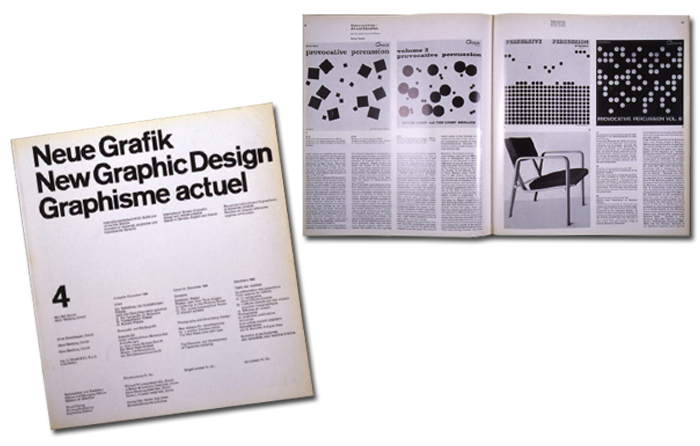

Ulm was austere and serious, focused on semiotics and what we would now call information theory, like a monastery filled with designers turned political activists. Like the Bauhaus, it was philosophically committed to a unified approach to products, graphics, and architecture. Among its faculty were designers and theoreticians like Max Bill, Tomas Maldonado, Hans Neuberg, and Josef Müller-Brockmann, and their journal, Die Neue Graphic, would become the bible of mid-century Swiss modernism.

Dan was there too. In his last year at Carnegie Mellon, a new faculty member, Ken Hiebert, fresh from the Swiss Algemeine Gewerbeschule in Basel, revealed a side of design that was very different from the prevailing “commercial art” training that characterized Carnegie Mellon, and most US schools at that time. Hiebert encouraged Dan to continue his studies in Europe. He won a Guggenheim Fellowship and chose to go to Ulm. But when the school collapsed in political strife a year later, Dan transferred to Basel, in 1968.

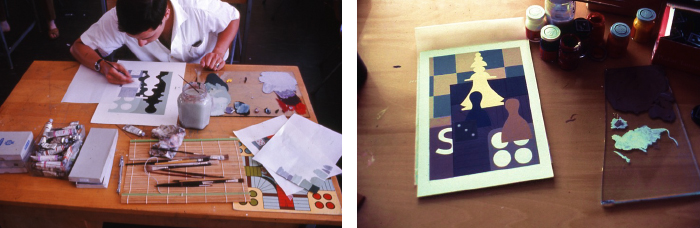

By chance, Esther and I wound up at Basel that same summer. As a new teacher at Yale I had been sent to see what their program might offer our own curriculum. Key among the school’s many gifted teachers was Armin Hofmann, who had been a periodic visitor to Yale since the 1950s. He welcomed us for six weeks to experience his school. In stark contrast to Yale, the environment at Basel consisted of long quiet classes focused on drawing, color, and formal exercises. It was all about process. Although Dan was there, we did not actually meet him.

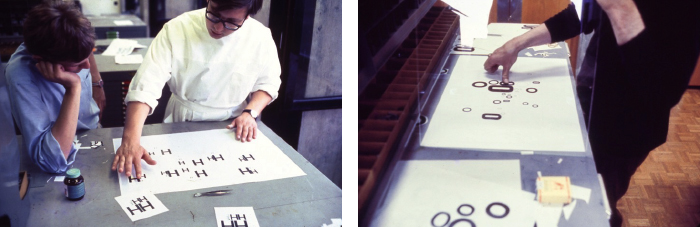

One person we did meet that summer was a young typography teacher in his first year there. Wolfgang Weingart, a classically trained German typographer in a white lab coat, had come to study under Emil Ruder, a revered modernist typographer and the school's director.

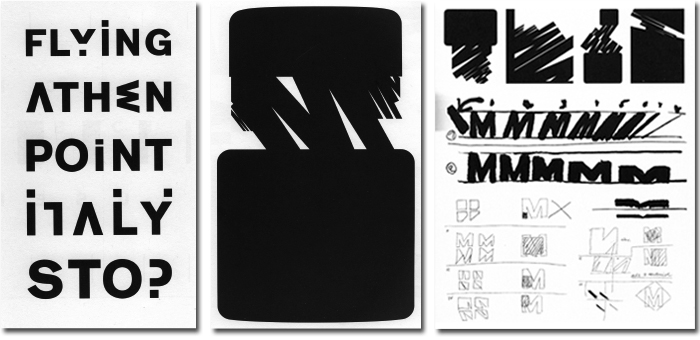

Weingart was steeped in the rigorous underpinnings of contemporary Swiss/German typography but suspicious of its impersonal, reductive bias. In his personal work he was searching for a more expressive, less dogmatic approach, and he found a like mind in Dan Friedman.

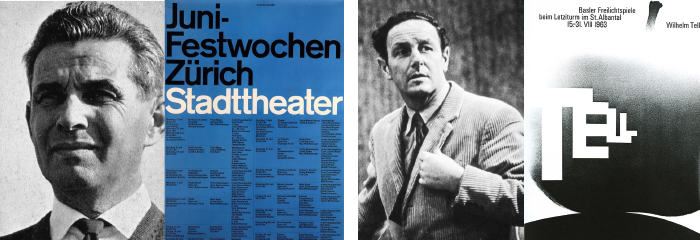

While it is tempting to lump all Swiss design of the 1960s into one category, that would be distorting the truth. The schools in Zurich and Basel, while an hour apart, were conceptually very different. Müller-Brockmann and the school in Zurich were more linked to the tradition of Ulm: cool, rational, systematic, scientific, applied.

Hofmann and the Basel school seemed, by comparison, more humane, intuitive, introspective, drawing- and craft-based, imbued with an aesthetic asceticism that Weingart's arrival leavened with a new and unconventional experimental energy.

By the end of the 1960s, these two pedagogical and formal approaches were diverging in a dramatic way, one that would play out over the course of Dan's career.