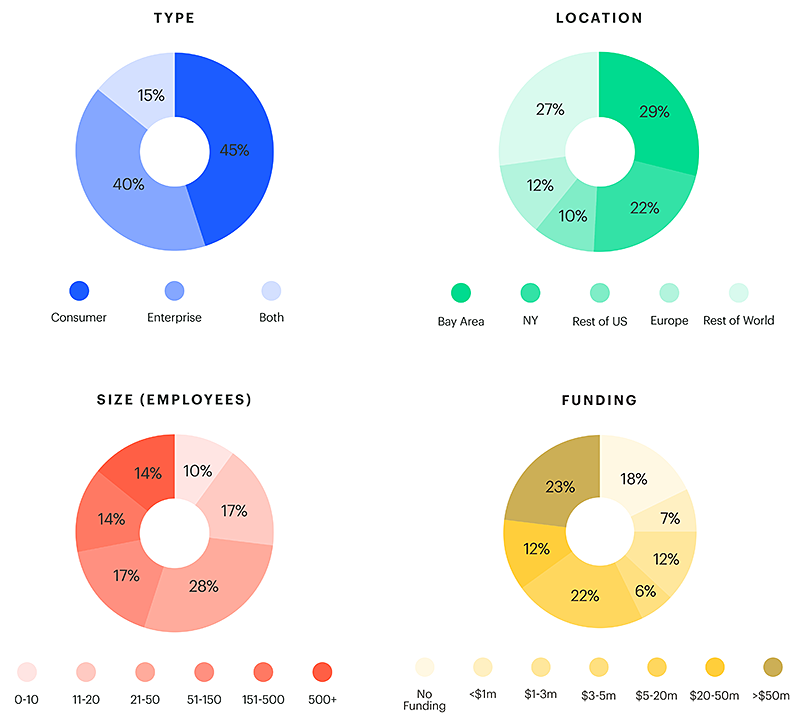

An overview of the companies surveyed in NEA's “The Future of Design in Start-Ups” report.

A few months ago, Doug Powell, Distinguished Designer at IBM, talked to Albert Lee, from the venture capital firm New Enterprise Associates, or NEA. Albert is one of the co-authors of “The Future of Design in Start-Ups,” a report created by and released recently by NEA. It presents a wide variety of data about the influence of design in the tech industry, in particular in the startup sector. This is part one of a two-part series.

Doug Powell: If you could, tell us a little about NEA as an organization, its mission and focus, and maybe a bit about what your role there is.

Albert Lee: Absolutely. NEA has the distinction of being one of the world’s largest venture firms, with nearly $17 billion in committed capital. And that means is that the NEA portfolio is very large. As a designer, I find two things really interesting about that.

First, the scale allows NEA to invest across any sector, from enterprise, to med-tech, healthcare, and biopharma; deep technology companies, like those working on quantum computing; and a robust consumer practice, with companies such as jet.com, Casper, the mattress company; design centered companies such as 53, and Onshape; and lifestyle brands like GOOP.

Second, the scale allows NEA to invest at any stage—we’re stage agnostic. So we can invest early in a company, like Casper, and also invest much later in an established company, like Uber. That allows me as a designer to see how design and product problems gestate from a seed-stage company to a far more mature company.

So, I’m kind of a kid in a design challenge candy store, because there are design problems across multiple sectors, in multiple stages, touching hundreds of different user personas.

DP: I imagine there’s a lot there, just thinking about the role of design in an early stage start-up versus the example you gave of Uber, a well-established working brand with a massive user base. The design challenges in each of those must be vastly different.

AL: Hugely. In the early stages it’s “What are we building?”, “How do we find product market?”, and “How do I build a team? How many designers do I need? Do I even need a designer? How does a designer work closely with an engineer?” Then, if the company does find product market fit, and they find a growth moment, the problems continue to evolve. In the later stages, if you are an Uber or an AirBnB for instance, you have these massive design teams, working on huge releases. So from a design standpoint: What does that look like, and what kinds of problems are you solving? There’s a lot of richness in challenges at every stage.

DP: Talk about “The Future of Design in Start-Ups” report, why did you undertake this project?

AL: I have a really close collaborator at NEA, Dana Grayson. She’s invested in companies like 53, Pocket, and Onshape, and she was a product designer in her previous life. She’s been tracking this space for a really long time as an investor. I’ve been tracking it more purely as a designer. One of the things that we’ve observed is that there’s a ton of interest, as well as an upswell of support within the startup and technology world for design. Design should have a seat at the table. No one refutes that. What’s been really interesting to us though, is that there’s been a dearth of data. Actually, there’s been almost no data that’s been gathered around how design operates, why you might want it to be in your startup, and when you might want to deploy design in different ways. So we wanted to get some insight into how integration of design actually occurs in company operations, alongside the more traditional silos of product, and engineering, and marketing, and sales.

A breakdown of the maturity of survey responders.

DP: In the report you pay a lot of attention to the maturity of a company. How do you qualify maturity in the context of this research?

AL: When we put out the survey, our hope was to collect a large enough data set to understand how design might be operating. We were quite lucky. Our responses had good coverage across size of company, stage of growth (which we looked at primarily through the lens of amount of capital raised), type of company (pretty much an equal split between consumer and enterprise), and geographic distribution (which was also pretty evenly distributed).

Of all our responses there were 302 companies that qualified as “design-centric.” These are companies that have you raised some capital, and consider design as a critical part of their business. Once we had that core group of design-centric companies, we split that into three further groups.

The main group was one that we called “design committed.” This consisted of 96 companies that said design was “very important” to the business, and that either had a designer as co-founder, or at least five designers on staff. In other words, they had doubled down on having design leadership at the get-go at the very top, or they had built out a sizable design team during the time of their growth.

When we looked at that group, we realized that there’s actually another smaller group within those 96 companies, which we called “design mature.” And this was probably the most interesting. These are companies that said design was very important, but that also had more than $20 million in funding and at least 20 designers on staff, which is a lot of designers for a startup. That means there was a level of investment in design leadership, design within their operations, the product development process, and culture. We were really curious about that particular group and what they said in response to some of the questions we posed.

And if you go even deeper, within that group, there were 8 unicorns. These are “design-mature” companies, with a valuation in excess of a billion dollars.

What was most surprising, at a high level, if you look at the “design-centric” group, all the way from startup to mature, almost across the board, the importance and level of value that these companies put toward design increased. So if you take a step back, it’s kind of saying that larger companies, those that have experienced a certain type of success in the marketplace (and it’s not necessarily about capital raised or valuation, but about a certain amount of sizable growth, in terms of company and employees), all pretty much look around after they’ve achieved a certain level of success and say, “You know what? Design helped us get here. And investing in design at the beginning was critical for us to find out way to this particular point in time in our company’s evolution.” That was probably one of the most heartening high-level insights, or trends that we saw coming out of the report.

DP: Was that surprising to you? Or was that part of your hypothesis going in?

AL: I think we had all hoped it would be so. We just didn’t know it would be so clear-cut. Our hypothesis was: We will have a group that says, “We absolutely believe in the value of design.” We just didn’t know there would be so many successful companies, with such large design teams, that we would be able to tell the story around. That was exciting.

And these aren’t just folks who say they love design and are tinkering with a product. These are folks who have built products of massive value with hundreds of thousands and millions, if not millions and millions of users.

DP: What qualifies as design? What are the boundaries around “design” that you placed?

AL: If you look at how design has evolved through the lens of the technology startups, for many, many years we had very engineering driven cultures. Engineers would often be the company founder. Engineering would often be the lifeblood of innovation within the company, and critical to the success of the company.

Yet over time, the way to differentiate your company started to rest on creating products for many different kinds of end users, and design moved from not being just about UX and wireframes, or just UI, or how the thing looks and making things pixel perfect, but it also began to include user research, qualitatively how we understand the needs of the end user and the various use cases and personas tied to that, as well as visual and brand marketing. So design now is integrated in every aspect.

A side note is that writing and copywriting have become part of the design family within technology startups. So the language is important. If you look at a product like Slack, so much of the experience is its voice and tonality—what Slackbot says to you. I’ve been asking a bunch of heads of design at various companies, “Is writing part of design?” They say yes, that writing is a core medium within the design team now. I think that’s neat.

DP: Our experience here at IBM mirrors that. We’ve been a bit naively ignorant of the value of the writing skill set when we launched our program four years ago, and just in the last year we’ve reevaluated and included writing explicitly, partly because we saw the void and the need, and partly because some really great natural writers, who weren’t really defined as such when they came into the organization, came to become really valuable people and their contribution was hard to miss.

You also have one part of the study that is about speed to market. How does design make companies and teams work faster?

AL: This answer will be coming from both a bit of what we heard in the survey, but also some anecdotes I’ve observed within the NEA portfolio. If you think about how design can add value within a really fast moving entity like a startup, two things always come up. One is process, and the other is clarity.

By process, design often allows for really, really rapid iteration cycles, with designers switching quickly between making things and getting feedback. That type of thinking and that type of modality have always been a part of startup culture. We’ve seen it in recent startups, but it goes all the way back to the halcyon days of Silicon Valley: Fail fast and often. But designers in particular that operate that way are often brought in at the very beginning of the process, and that often leads to increased velocity, as opposed to talking ad infinitum about what should get done.

The second is clarity. What I’ve heard is that through tangibility—making the thing, or prototyping the thing—allows for multiple parts of the organization to huddle around an actual artifact with clarity and say, “Ok, this is what we should do next.” Design often has a role to make things tangible.

DP: Can you tell me more about design having a seat at the table?

AL: One of the things that we frequently heard in the survey was that for design to be recognized as an integral part of the product, it isn’t just about having a seat at the table. It's not enough to ensure that the voice of the user is heard, but to create an integrated mindful experience. Design should work in a true end-to-end experience and ideally is integrated across all company operations. That means, for example in marketing: ad banner units, and emails that go out to a user, all the way to the conversion moment, and then into retention. Having design in every aspect creates tangibility and a more unified and clarifying road map for how all of those efforts can be tied together.

In part two of this interview, Doug and Albert discuss the tangible values design can bring to a company, ideal team structure, and finding the right talent for design leadership.