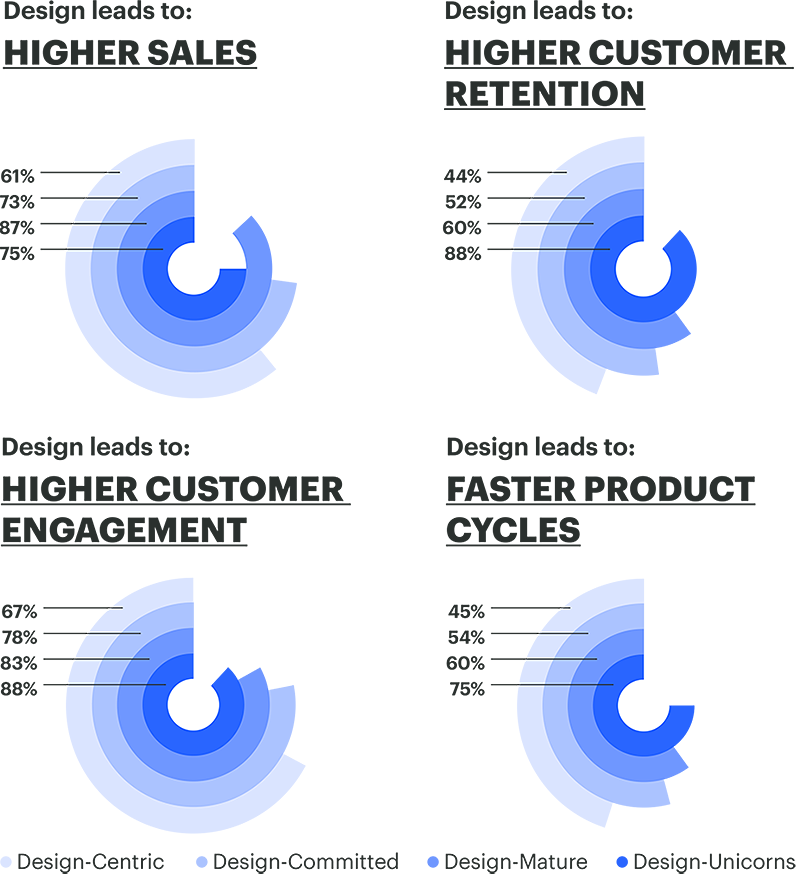

How design impacts business. Across all key questions, in the NEA "The Future of Design in Start-Ups" survey, the more mature companies reported greater impact of design.

This is part two of Doug Powell's interview with co-author of "The Future of Design in Start-Ups" report, Albert Lee. You can read part one here.

Doug Powell: It's really great to hear, and to see as part of the survey, that in industry leading companies design is ideally integrated across all company operations. That’s one of the battles that we continually have to fight here at IBM as we embed a new way of working in a culture that is not used to working in a design-driven way.

The feedback we get a lot is, “We just don’t have time for design”. What I’m seeing in the responses is that a high-functioning team, a team fully staffed for design, is working faster ,and driving outcomes into the market faster. Second, they have a much higher level of confidence that they’ve hit the target with what they’re driving into the market, because they’ve got real feedback from real people.

Albert Lee: That’s such a great point. I was talking to a head of design at one of our enterprise companies the other day, and he said, “What can sometimes be frustrating is that design can be perceived as expensive by some of my collabortors.” There's a mindset that it costs more, and it’s thought of as something that happens at the end of a process. You figure out what you need to do, you build it, then you put a bit of lipstick on it, and you push it out the door. It’s like a cherry on top. But if we’re going to ship a sundae, we don’t really need the cherry on top, the ice cream is what they’re buying.

Part of what you know innately, Doug, and where you’re driving change at IBM, and also what the survey shows, is that having design at the very beginning of the cycle—including a designer or product designer early on—helps de-risk the business. This is true both within a small product cycle, but also within the larger arc of a business.

We see this often in the early stage companies. If you utilize key design principles, be user-centered, et cetera, it actually de-risks the business. So the target area actually gets smaller, and the number of cycles that it takes to get to an answer to your hypothesis grows fewer. We’ve seen that proven time and time again. It’s super cool to hear that you are enacting that type of change, because you guys are huge. I hear you have hundreds of designers now.

DP: It is both cool, and enormously challenging. Just to close out that thread of design being expensive, what’s really expensive is putting a product with lousy user experience out in the market and seeing it just sink like a rock. That’s expensive, and that’s unacceptable.

Let’s change gears and talk about teams and team composition. You’ve got a great section in the report about team building. That’s something that we’re really studying here at IBM. We’ve got this great laboratory of design teams and what we’re finding is that emerging technologies—AI, virtual reality, IoT, and the like—initially require a more complex team structure than in the past. What have you found about what the modern design team needs to be successful?

AL: One of the things we heard, with a pretty clear signal, was that as companies get larger and more mature they transition to a pod or a squad structure. There’s a difference between what pods and squads are, but for the sake of the conversation, I’m lumping them together.

This phenomenon was made famous by some work that Spotify had done. They essentially said, “We’re going to create a very small startup within our company, because we’re a few hundred people, going on a thousand, and we need to move faster.” So rather than say that there’s going to be a single design service bureau that’s going to be collaborating with all the various parts of the product, they planned to take parts of the product and give it to smaller teams. And within those smaller groups, there would be a design lead and a small design team. Tying all the small teams together would be design leadership that would oversee, mentor, and support all of the design teams.

In the future, we hope to address the following: How do you shift to pods and squads? When do you make that shift? Some design leaders have told me that their design teams are unhappy being across all these pods, while other folks say it’s great, that it allows them to move much faster. But overall, it does appear to be the optimal structure to end up on. If you’re working on products that have a lot of technologists involved, and you are prototyping very quickly, it makes sense for there to be more of this pod-type structure with designers dedicated to moving even faster.

DP: It’s a fascinating area and we’re just completely geeked out about it here, because we’ve got a lot of teams that are intoxicated by the notion of the Spotify model, if you will. And they all went deep around this “how can we organize around the pod or squad and tribe” question. Now we’re a year in and it’s certainly stuck with some teams, but it tends to buckle a little under scale. We’ve got some design teams that are in the hundreds here, and that’s where it seems to get shaky at the knees. But it’s fascinating to pick that apart and see how that operates. It’s interesting to see how those teams—regardless of how they are structured—connect with product management, engineering, sales, marketing, and all of the other functions that are required for a really robust product organization.

AL: From startups to larger companies who have been traditionally engineering drive there's an important question: How do you create a design culture? Because when it goes badly, the design team becomes a service bureau. It becomes reactionary to the needs of the company. Then the product development team says they want this, the marketing team says they want that, tickets are flowing in, and the design team can’t keep up. Essentially, it’s like a print shop. It’s not great. But when it goes well, design has an equal seat at the table, on par with product and engineering.

The other day, I asked Randy Hunt, VP of Design at Etsy, “What is the most important thing that you guys have done to make sure that design is integrated in the right way?” He said, “Creating really, really tight relationships across my peer set, so that we can take risks and mess up, and still have everyone ok with that.” This ties to the “design is expensive” thing. He’s created air cover for his team to be able to build its culture, but also to push the company to iterate and experiment.

At some point in a company’s journey, if there isn’t already a design leader in place on the executive team who can advocate for design both in a qualitative and quantitative way, that company can really struggle. Ensuring that such a design leader is either nurtured from within or without is a critical piece.

DP: This is very interesting, and I agree with Randy Hunt. He is something of a prototype for the type of design leader that’s really needed in this space now. Everything for Randy starts with design and being a designer. Where that leadership comes from is such a puzzling question, though. I know it’s a big question for AIGA. It’s a big question for us here at IBM because we’ve hired most of our design talent, and we’ve hired almost 1,000 entry-level designers. But how do we populate the middle ranks of leadership in a scaled design organization? That’s really a big challenge for us right now.

AL: We’re also seeing that challenge in the technology startup world. There’s only a handful of folks who have seen a product and company go through all of the stages of development. Take a guy like Shalin Amin, who’s head of design at Uber. He was there at the very beginning, when they did mobile app v1.0. And he’s been able to grow a large and impressive design team there. But there are only maybe 20 to 30 people who have that level of experience. However, we are seeing an entire generation of designers who have left agencies, or who have come out of school and gone straight into launching products in startups, or have dabbled in starting their own things. We’ll start to see leaders emerging from that in pretty exciting ways.

DP: Speaking of the people and talent aspect, what did you find as you mapped out the design disciplines that are in demand?

AL: This one is pretty clear: It’s product designers, despite a lack of definition of that job title. In the next survey, one of the things we’re going to collect is a broad definition not just of design, but also of product design, and user experience.

We all knew that product design talent was highly in demand, but we didn’t know how much growth teams were planning for. Almost everyone is growing by at least 50 percent, and this isn’t even including the Googles and the Facebooks and the IBMs of the world, who also value design in a really big way. The need for talented designers is increasing and it’s reaching a fever pitch. Technology startups are eager for product designers who can do UX, UI, prototyping, and can think about a product holistically. Those designers who can think in the center of the user needs, business needs, and engineering capabilities. That’s top of mind for everyone, from early-stage companies to the unicorns.

Another interesting thing that we found is that there’s an emerging ratio of how many designers you want in your company. Most people believe that the golden ratio is one designer to five engineers. That’s fewer engineers per designer than most companies have organized around in the past or present, which is another indication that design talent is going to be in greater demand.

DP: We’re at a place of about 1:8 or 1:10, depending on the business face, and we’re very sensitive to that 1:5 zone. We attribute the slightly higher number to the complexity of most of the technology that we’re working on. By necessity, we have some pretty high demands on the engineering side.

AL: It sounds like you have a specific set of needs there, and that makes a lot of sense. It’s been such an interesting topic to get numbers on: “How many designers we actually need to support all these products that are coming to market” and “Is the next generation of designers are being supported in the right way?” Last summer we ran a program called “Design Residents,” where we had a call for talent from design schools across the U.S. We placed the students inside of NEA companies like Jet.com, Casper, 53, Engima, and Glamsquad. What quickly became apparent was that they had skills that could be deployed, but there was not an immediate understanding of how to operate within a fast moving startup. It’s like they understood prototyping, and they understood all the mechanics, but they had no context for what it means to work within a rapidly growing company, which makes a lot of sense. I mean, how could they? I do think that there’s a real opportunity to create a clear pathway between design education and the opportunities that exist in a more explicit way than has been happening now.

DP: I couldn’t agree more. A big part of our program at IBM is a three-month bootcamp that we’ve built for our entry-level designers with that express intention. We call it the missing semester of college.

AL: Sounds cool! I want to take that.

DP: Come down and check out our program! It’s exactly what you’re talking about. We’ve come to terms with the fact that if we’re going to invest in entry-level talent—partly out of necessity, but also for a variety of other reasons—then we can’t rely on the academic community to meet our needs. They move slowly. There are very few truly stand-out programs that absolutely hit it on the head, and we need to anticipate or expect that a graduate from a great design program will come in the door with some gaps in their skill set that we need to fill.

AL: I am so curious that I am going to bug you for more about that missing semester. It sounds highly valuable, and those designers sound lucky.

You can find "The Future of Design in Start-ups" at www.futureof.design.