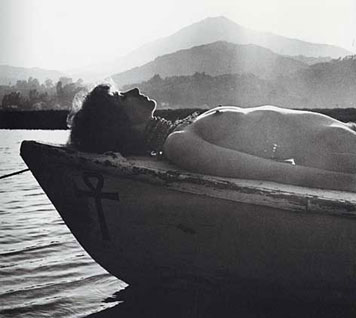

Photograph by Wallace Berman, "Shirley Berman," Larkspur 1960

The mystery of Wallace Berman's photographs revolves around the degree to which they were — or were not — set up. Was Berman attempting to create a narrative, or was he simply recording the people and events he saw around him? There's a great deal of play-acting in his photographs, and one wonders how much of it was staged, and whether or not Berman was the director of the action. Was performing for each other simply part of how he and his friends related to one another, part of the social routine, a communal project experimenting with identity, or was it all Berman's invention?

In 1961, Wallace Berman, a California-based artist, publisher of the proto-zine, Semina, gallerist, and photographer, took a picture of his landlady while he was living in Larkspur, California. We see her (the landlady!) sprawled across a bed dressed in a bra and skirt, casually holding a pistol. Clearly, this picture is not likely to be documentary (unless the rent was really late); it's better described as a photographic fiction, and one wonders what the nature of that collaboration between Berman and his landlady was. Whose idea was the gun? The question about collaboration is particularly pertinent to the numerous photographs that Berman took of his wife, Shirley, who was the subject of some of his most imaginative pictures. One wonders just how much she brought to them in addition to her extremely beautiful physical presence. One of Berman's most potent mythological works is his image of Shirley, unclothed and shot in profile, stretched across the bow of a boat with an "ankh" painted on its side. The picture evokes a reverie of oneness with the earth, as the profile of Shirley's body is echoed by three mountains in the distance that are shrouded in mist. The ankh (an old Egyptian symbol for life) appears here in its new age context, very much of a piece with the rest of the picture, underlining the artifice. This picture is one of many collaborations between Wallace and Shirley that document constantly varying notions of what constituted erotic allure.

The mountain that echoes Shirley's body in the picture looks a lot like Mount Tam, a landmark in Marin County. Many of Berman's pictures are set in evocative urban spaces or landscapes in California that are weathered and run down to such a degree that they've assumed an air of decayed grandeur. Today, places like Venice Beach or Marin try to maintain the mystique of the rusticity they once embodied, which Berman both documented and used, but of course that patina has vanished: this only serves to intensify the sense of a lost world, of a weather-beaten, poor California that can be seen in Berman's pictures.

While these lost landscapes provide a stage set for Berman's artifice, there was nothing false about the people he photographed. In their play-acting we witness them work at, or rehearse, a vision of an alternative society. In looking at Berman's pictures it's obvious that these people had lots of ideas about how to create their own lives independent of the mainstream culture that by the 1950s had become an oppressively pervasive presence in American media. They truly were operating outside, but it wasn't an outside based on criminality — it was an outside based on valuing aesthetics, freedom and independence from expectation. This isn't to suggest that none of these people had problems. Many of them did, often with drugs, and there was a lot of acting-out opposition to mainstream society in ways that were self-destructive. You can see that in the traces of sadness and depression that run through some of the pictures. This is not part of the artifice, but a sign of a life authentically, if not easily, lived.

The New York Times Sunday Magazine recently devoted an issue to what they referred to as "the new bohemia." In paging through it I was struck by the fact that every person it featured had something to sell, and that whatever genuine meaning the word "bohemia" once had has been completely drained away by contemporary forces. Things may come clothed in the image of rebellion (and Berman's pictures certainly provide a study guide for that) but that idea of truly separating yourself, or crafting a life detached from the dominant culture has been lost. The bohemianism of Berman's community was rooted in an independence based on valuing a life of the mind and a life of beauty, and they were willing to pay the full price of admission to live that way. They didn't choose to live the way they did in order to be admired, and didn't care if they were on anybody's radar. The notion of anonymity — which is something the Berman circle cherished — is completely anathematic to artists today. Maybe it's just too frightening right now.

The question of whether there are artists today making pictures that delve into ideas similar to those in Berman's work pivots on that question of how much he staged his pictures. If they were completely staged, and Berman was the author of the staging, then artists like Gregory Crewdson and Philip-Lorca diCorcia are obviously his heirs. If the pictures are primarily documentary, then the work of Nan Goldin comes to mind. It's hard to say exactly who his grandchildren are in terms of his photography. However, the one thing you can say unequivocally is that the kind of community he collaborated with, and documented so lovingly — the way it operated and the values it represented — is long, long gone.

This essay was originally published as the afterward in Wallace Berman: Photographs by Kristine McKenna and Lorraine Wild (RoseGallery Los Angeles, 2007).

Comments [15]

That said, the real loss is truly iconoclastic beauty.

09.12.07

10:10

09.12.07

10:59

09.12.07

11:55

The comment about today's expo on boho having to do with commerce is fascinating - but - instantly I assume these photos were of bohos in NYC? A very different breed than those in a canyon community out West.

In terms of Crewdson (who I also love) his images are so elaborate and psychological, one scans his images for clues, they read long and slow and resonant. But they too have an outsider feel and appear, high-brow and rich, a comment on others from a priveledged (wealthy) perspective. The viewer doesn't feel like a part of the scene but rather, like an examiner on CSI, peering in with objective neutrality.

As for boho, I think today's response could be in film. There's the play-acting and the self-conscious awareness of being watched (as a subject), but there are many directors/journalists seeking out alternative communities, seduced by the group belief and compelled to live with and document their adopted world. One example is David LaChapelle's Rize. It's a different kind of boho, urban, violent, erotic, and purely about community.

Just some thoughts...

09.12.07

12:03

09.12.07

12:11

09.12.07

12:28

are long, long gone

09.12.07

02:00

I also love the rustic view of the locales. I live in NorCal and can tell you that most -- if not all -- of the locations pictured have morphed from simple towns to exclusive enclaves. A lost era, indeed.

09.12.07

04:26

09.17.07

11:42

09.26.07

02:47

Anonymity seems like the crux for me - whether we are doing something for ourselves, for the internal experience of it, or for the external image or perception of us that we hope it creates in others. Documenting something, taking pictures or films, almost by definition presupposes the mindset of being observed, that the external, temporally displaced perception is what matters rather than the internal, in-the-moment one. In today's highly produced, mediated world, so many people seem to be seeking a genuine experience, and are drawn to those who seem to be having them... but the second that we care how we appear to others and whether we are being recognized, we have lost that genuine internal experience.

Berman's photos capture the aura of a genuine experience, and I hope for the sake of those who made them that that's what it was.

09.28.07

10:55

10.04.07

02:33

10.04.07

03:07

Fair enough. I wasn't around at the time. I was just responding to the article's notion that Berman & Co. valued anonymity:

They didn't choose to live the way they did in order to be admired, and didn't care if they were on anybody's radar. The notion of anonymity — which is something the Berman circle cherished — is completely anathematic to artists today.

... and that for some reason Wild chooses to demonstrate that artists today don't value anonymity by referencing the NYT co-option of "bohemia." Maybe, just maybe, those artists that do value anonymity chose not to be in the NYT article.

10.16.07

09:57

I distrust my own intuition, falsified by the same nostalgia that gives rise to it, but something in these photographs reminds me of the Sunset Magazine aesthetic that powerfully guided many in the 1950s and early 1960s — redwood, zen like backyard landscape designs, camping, tiles from Mexico…

the John Birch Society family I grew up in was certainly not boho, but at this great distance I sense some connection between these different worlds.

06.23.12

09:36